The Hand of God (2021): between Sex and Maradona | entre el sexo y Maradona [ENG | ESP]

Last March, I had my first encounter with Paolo Sorrentino thanks to his excessively beautiful film Parthenope. Three months later, I saw the film that won him the Oscar for Best International Feature Film, the celebrated La Grande Bellezza, where I confirmed some of the traits of this director's work that I really like: the humor, the cinematography, the combination of comedy and tragedy, and especially the very, very Italian characters and stories.

El marzo pasado tuve mi primer encuentro con Paolo Sorrentino gracias a su excesiva y hermosa película Parthenope. Tres meses después vi el film que le valiera el Oscar a Mejor Película Internacional, la celebrada La Grande Bellezza, en donde confirmé algunos rasgos del trabajo de este director que me gustan mucho: el humor, la fotografía, la combinación de comedia y tragedia y en especial, personajes e historias muy, muy italianos.

I then wanted to review the rest of his filmography and remembered that a few years ago Sorrentino was nominated for an Oscar again thanks to È stata la mano di Dio (The Hand of God), which I was able to see a couple of nights ago. The film tells the story of Fabietto Schisa, known as Fabié, a seventeen-year-old boy who lives in Naples with his family in the 1980s. It's a coming-of-age film, about that transition between childhood and youth, as Fabié begins to discover the world beyond his family's social circle and begins to think about what to study, what he will do for the rest of his life. The young man's interests are many, but mainly three: philosophy, whose classical authors he often quotes in various conversations; sex, embodied above all by Aunt Patrizia, his uncle's wife, who seems to have certain sanity issues and whose behavior has worried the family to the same extent that her curves and maturity have mesmerized young Fabié; and soccer, a sacred sport in the city, which is revolutionized by the greatest news it had experienced up to that point: Napoli has managed to sign the Argentine star Diego Armando Maradona. Fabié's visits to the stadium to support the city's team and watch the man who would later become world champion and the leader who would lead Napoli to win the Scudetto and other trophies alternate with family gatherings, the Italian summer, the sea, the promise of dreams, and also the betrayal of reality.

Quise entonces repasar el resto de su filmografía y recordé que hace pocos años Sorrentino volvió a estar nominado al Oscar gracias a È stata la mano di Dio (The Hand of God) la cual pude ver hace un par de noches. En la cinta se cuenta la historia de Fabietto Schisa, a quien llaman Fabié, un joven de diecisiete años que vive en Napoli con su familia en los años ochenta. Se trata de una película de iniciación, de ese tránsito entre la niñez y la juventud, ya que Fabié comienza a descubrir el mundo que se mueve más allá del círculo social de su familia y comienza a pensar en qué estudiar, qué hará el resto de su vida. Los intereses del joven son muchos, pero principalmente tres: la filosofía, cuyos autores clásicos suele citar en diferentes conversaciones; el sexo, encarnado sobre todo en la tía Patrizia, la esposa de su tío que parece tener ciertos problemas de cordura y cuyo comportamiento ha preocupado a la familia en la misma medida en que sus curvas y su madurez han hipnotizado al joven Fabié; y el fútbol, deporte sagrado en la ciudad que se revoluciona con la mayor noticia que hubieran vivido hasta entonces: el Napoli ha logrado fichar al astro argentino Diego Armando Maradona. Las visitas de Fabié al estadio para apoyar al equipo de la ciudad y ver jugar al que posteriormente fuera el campeón mundial y el líder que llevaría al Napoli a ganar el scudetto y otras copas se van alternando con reuniones familiares, el verano italiano, el mar, la promesa de los sueños y también la traición de la realidad.

As in Parthenope and La Grande Bellezza, the city—Naples in this case—is another character. The wide-angle shots or shots from terraces, the alleys, the parties, the coast... watching a Sorrentino film—or at least the three I've seen—is also falling in love with a city and wanting to explore its spaces. Just as when you watch Before Sunrise and want to walk through Vienna or explore the French capital after seeing Midnight in Paris, you want to go to Naples after seeing È stata la mano di Dio.

Al igual que en Parthenope y en La Grande Bellezza, la ciudad - Nápoles en este caso - es un personaje más. Las tomas abiertas o desde alguna terraza, los callejones, las fiestas, la costa... ver una película de Sorrentino - o al menos las tres que he visto - es también enamorarse de una ciudad y querer recorrer sus espacios. Tal como cuando uno ve Before Sunrise y quiere caminar por Viena o recorrer la capital francesa después de ver Midnight in Paris, dan ganas de ir a Nápoles después de ver È stata la mano di Dio.

Fabié's age is also important for the development of the plot and the character. In countries where the age of majority is 18, 17 marks the threshold of adulthood, not only because of its numbers, but because it coincides with important changes: the end of high school, the beginning of university life, the first sexual experiences occurring around that age for most people, the end of childhood... 17 is the turning point in a person's life, when they still have the energy to dream big, when their innocence—usually—hasn't been so corrupted, and that mix of emotions, hopes, and dreams mean that at that age, one is not yet an adult, but neither is one still a child or a teenager. In a way, it's the last age, or the last stage in which, without being any of those things, you can possess attitudes of both and not trigger criticism from your surroundings. Just as tenderness, innocence, and playfulness seem like signs of immaturity in very adult people, seriousness and tragedy don't seem to us to be characteristic of childhood; but at 17, it's permissible to be both and neither at the same time. And Fabié is like that, and that makes him charming on screen, whether he's sharing a family lunch with his father, or riding the streets of Naples on a smuggler's motorcycle, or crossing the sea at dawn to go to Capri, or sleeping for the first time with a woman much older than him.

La edad de Fabié también es importante para el desarrollo de la trama y del personaje. En los países en los que la mayoría de edad es a los 18 años, los 17 constituyen el umbral hacia la edad adulta, no sólo por una cuestión numérica, sino porque coincide con cambios importantes: el fin de la secundaria, el inicio de una vida universitaria, las primeras experiencias sexuales se dan alrededor de esa edad en la mayoría de las personas, el fin de la infancia... los 17 años son el punto de inflexión de la vida de una persona que aún tiene energías para soñar en grande, cuando su inocencia - normalmente - no se ha visto tan corrompida y esa mezcla de emociones, esperanzas y sueños hacen que a esa edad uno no sea aún un adulto, pero tampoco se siga siendo un niño o un adolescente. De alguna manera, es la última edad, o la última etapa en que sin ser ninguna de esas cosas se pueden tener actitudes de ambas y no desatar la crítica del entorno. Así como la ternura, la inocencia y el juego se nos hacen señal de inmadurez en gente muy adulta, la seriedad y la tragedia no nos parecen propias de la infancia; pero a los 17 años está permitido ser ambas cosas y ninguna a la vez. Y Fabié es así y eso lo hace encantador en pantalla, ya sea que comparta un almuerzo familiar junto a su padre, o recorra las calles de Nápoles en la motocicleta de un contrabandista, o cruce el mar en la madrugada para ir a Capri o se acueste por primera vez con una mujer mucho mayor que él.

The incisive dialogue, the humor, the religious theme, youth and old age, death, the beauty of Naples, the Italian idiosyncrasy, family, the sea, the love of cinema, the search for identity, the promise of the future, rites of passage, the passion for football, the philosophical dilemmas... all of this is present in the script of this film that lasts a little more than two hours and that feels at times like a play, sometimes like a painting, sometimes like a myth, a legend, like a dream, but that at all times makes us feel in the presence of the best cinema.

Los diálogos incisivos, el humor, el tema religioso, la juventud y la vejez, la muerte, la belleza de Nápoles, la idiosincrasia italiana, la familia, el mar, al amor al cine, la búsqueda de la identidad, la promesa del futuro, los ritos de paso, la pasión por el fútbol, los dilemas filosóficos... todo eso está presente en el guion de esta película que dura un poco más de horas y que se siente a veces como una obra de teatro, a veces como una pintura, a veces como un mito, una leyenda, como un sueño, pero que en todo momento nos hace sentir en presencia del mejor cine.

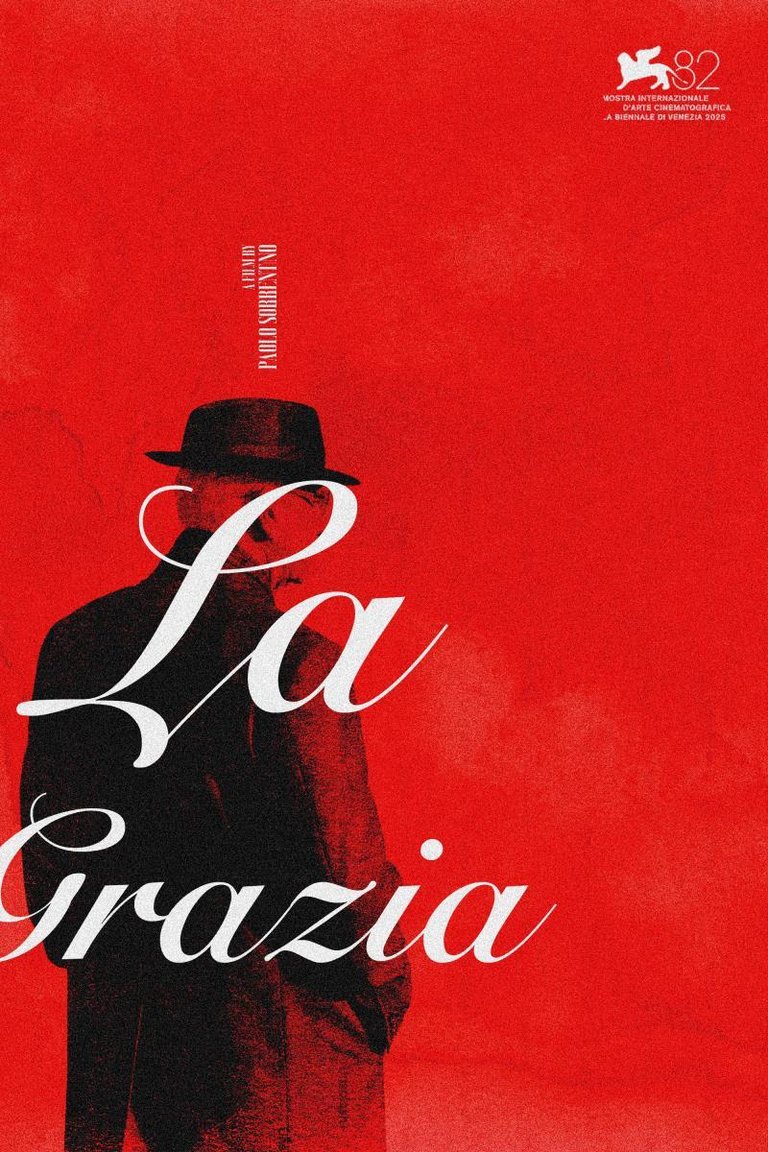

Maybe I'm a bit biased, but I feel that Italian storytellers have a common soul. Although each has his own style, I feel something emanating from them that is similar to all of them, and it applies to screenwriters, film directors, and novelists alike. When I read a book by Alessandro Baricco, Erri De Luca, or Niccolò Ammaniti, I imagine it as if it were a film by Federico Fellini, Sergio Leone, or Paolo Sorrentino himself, because the musicality of the prose, the humor, and the beauty of the images described on paper are so similar to the spirit of what the other names mentioned show us on screen. There are a couple more Sorrentino films I'd like to see soon, Le Conseguenze dell'Amore and La Givinezza, before La Grazia, his latest film, hits theaters. That film premiered this year at the Venice Film Festival, and all I know is that it's a political drama, so I'm interested to see what Sorrentino's approach is like when it comes to writing something different from what I've seen from him so far. I know the cinematic universe of the cradle of the Roman Empire is endless, but I also know that this platform is home to dozens of film enthusiasts and scholars, so I want to ask you: of all the Italian directors, actors, actresses, or films that you know or have seen, which are your favorites? Which ones would you recommend I see? Have you seen any other Paolo Sorrentino films that you'd recommend? I'll read you in the comments.

Tal vez esté un poco sugestionado, pero siento que los narradores italianos tienen un alma común. Aunque tengan cada uno su propio estilo, siento manar de ellos algo que es similar en todos y aplica tanto para los guionistas, como para los directores de cine y los novelistas. Cuando leo un libro de Alessandro Baricco, Erri De Luca o Niccolò Ammaniti, lo imagino como si fueran películas de Federico Fellini, Sergio Leone o del propio Paolo Sorrentino porque la musicalidad de la prosa, el humor, la belleza de las imágenes descritas en el papel se parecen muchísimo al espíritu de lo que los otros nombres mencionados nos muestran en la pantalla. Hay un par de películas más de Sorrentino que quisiera ver pronto, Le conseguenze dell'amore y La giovinezza, antes de que La Grazia, su última película, llegue a las salas de cine. Esa cinta fue estrenada este año en el festival de Venecia y todo lo que sé es que se trata de un drama político, así que me interesa ver cómo es Sorrentino a la hora de escribir algo diferente a lo que he visto de él hasta ahora. Sé que el universo cinematográfico de la cuna del Imperio Romano es infinito, pero también sé que esta plataforma alberga decenas de apasionados y eruditos del cine, así que les quiero preguntar: de todos los directores, actores, actrices o películas de Italia que conocen o que han visto, ¿cuáles son sus favoritos? ¿cuáles me recomendarían ver? ¿han visto alguna otra película de Paolo Sorrentino que me quieran recomendar? Los leo en los comentarios.

Reviewed by | Reseñado por @cristiancaicedo

Other posts that may interest you | Otros posts que pueden interesarte:

Other posts that may interest you | Otros posts que pueden interesarte:

|

|---|

Sin conocer este filme, gracias a tu crítica reseña, tenemos la posibilidad de interesarnos en él, conociendo algo de lo hecho por Sorrentino, uno de los más singulares cineastas italianos de las últimas décadas. Saludos, @cristiancaicedo.