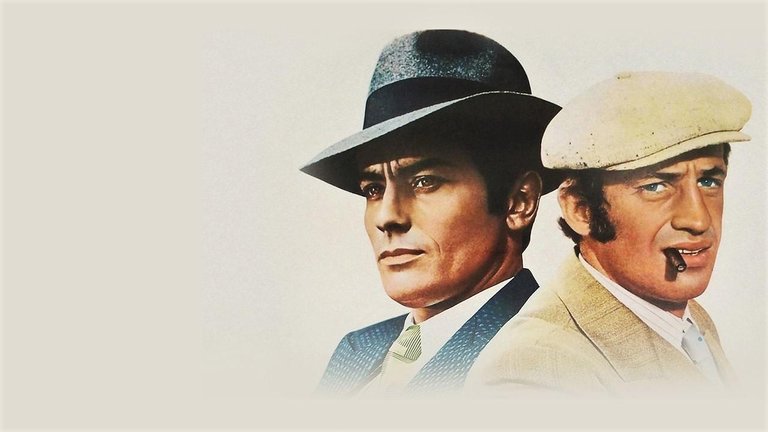

Film Review: Borsalino (1970)

The annals of cinema are littered with films that once commanded adulation and influence, only to diminish in stature as cultural sensibilities evolve. Jacques Deray’s Borsalino (1970), a lavish French gangster epic, epitomises this trajectory. Hailed upon release as a European precursor to The Godfather (1972), the film fused star power, period opulence, and underworld bravado into a box-office triumph. Yet, viewed through a contemporary lens, Borsalino emerges as a curious artefact—a work whose stylistic swagger and magnetic leads cannot fully offset its narrative superficiality and dated sensibilities. A fascinating but flawed relic, it encapsulates the paradox of a film simultaneously of its time and undone by it.

The genesis of Borsalino lies in the ambition of Alain Delon, then at the zenith of his fame as France’s preeminent screen icon. Inspired by Eugène Saccomano’s 1959 book The Bandits of Marseille—a non-fiction account of real-life mobsters Paul Carbone and François Spirito, who dominated interwar Marseille’s underworld and laid the groundwork for the French Connection heroin network—Delon envisioned a Hollywood-style biopic. Seeking to elevate the project, he courted Jean-Paul Belmondo, the rakish face of the Nouvelle Vague, as his co-star. Their pairing, akin to merging Clint Eastwood with Marcello Mastroianni, promised combustible chemistry. Yet the project’s transition from page to screen was fraught: when news of the adaptation reached Marseille, locals with ties to Carbone and Spirito’s legacy issued thinly veiled threats. Delon, heeding these “suggestions,” enlisted screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière to fictionalise the protagonists, transforming them into Roch Siffredi and François Capella. This pivot not only sidestepped the unsavoury reality of the duo’s WWII collaboration with the Nazis but also liberated the narrative from biographical constraints, allowing a mythic, if sanitised, reinvention.

Set against the sun-bleached backdrop of early 1930s Marseille, Borsalino chronicles the rise of Roch Siffredi (Delon) and François Capella (Belmondo), two small-time hoodlums whose rivalry over lover Lola (Catherine Rouvel) evolves into a bromantic criminal partnership. Their ascent—from rigging horse races to monopolising the city’s fish markets—unfolds with the swagger of a picaresque adventure rather than a gritty noir. Deray’s direction prioritises aesthetic grandeur over narrative depth, framing their exploits within Art Deco cafés and bustling harbours, Claude Bolling’s jaunty jazz score evoking the era’s decadent charm. The titular Borsalino fedoras, emblematic of the duo’s dapper menace, became a sartorial sensation, symbolising the film’s cultural cachet.

Yet the period veneer is intermittently compromised: hairstyles betray the late 1960s, and the script lacks psychological nuance. The women, notably Rouvel’s Lola, are relegated to decorative roles, their agency stifled by the film’s macho ethos. Political critique is neutered; scenes of corrupt elites consorting with gangsters gesture toward systemic rot but never interrogate it, rendering the film a visually sumptuous yet intellectually hollow spectacle.

The film’s enduring allure rests largely on its leads. Delon, all icy stoicism and lupine grace, embodies Siffredi as a man of few words and fewer scruples—a Redford-esque enigma. Belmondo, by contrast, channels Newman’s Sundance Kid, infusing Capella with roguish wit and physical bravado. Their dynamic, echoing the buddy formula of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), elevates even the thinnest scenes: a shootout, scored to Bolling’s buoyant brass, crackles with camaraderie, while their shared romantic entanglements—played for farce—highlight their contrasting personas. Yet their chemistry, though electric, cannot fully compensate for the script’s deficiencies, their characters remaining archetypes rather than fully realised individuals.

Where Borsalino falters is in its execution. Jacques Deray, later a stalwart of Euro-crime thrillers, directs with a dispassionate efficiency, prioritising glamour over tension. The pacing sags in the second act as Siffredi and Capella’s empire-building grows repetitive, their clashes with rival bosses Poli (André Bollet) and Marello (Arnoldo Foà) lacking visceral stakes. The script, allegedly coloured by Delon’s real-life entanglement in the Marković affair (a scandal involving his bodyguard’s murder), leans into the actor’s off-screen notoriety but shies from moral complexity. Michel Bouquet’s lawyer Rinaldi, a serpentine fixer, hints at institutional corruption but serves merely as a plot device.

The film’s finale, however, delivers a poignant swerve. Capella’s abrupt assassination—a betrayal by their own ranks—and Siffredi’s subsequent isolation inject unexpected tragedy. This denouement, both sentimental and stark, resonates as a rare moment of emotional weight, hinting at the deeper film Borsalino might have been. Deray’s decision to linger on Delon’s face—a mask of fury and desolation—suggests a self-awareness otherwise absent from the narrative.

Borsalino triumphed in Europe, its panache and star wattage eclipsing its flaws. Yet it faltered in North America, where Paramount’s hopes for a Gallic Godfather collided with cultural disconnect. The film’s afterlife is tinged with irony: Delon and Belmondo’s off-screen feud precluded a reunion, rendering the 1974 sequel Borsalino & Co. a diminished solo venture.

Despite its uneven legacy, Borsalino achieved a peculiar form of immortality. The film left an indelible impression on young Italian model Rocco Antonio Tani, who adopted “Rocco Siffredi” as his stage name, launching a legendary career in pornography. This bizarre footnote underscores the film’s lingering cultural resonance, albeit in a context far removed from its creators’ intentions.

Today, Borsalino stands as a captivating time capsule—a film that captures the allure of 1970s European cinema yet stumbles under the weight of its aspirations. Delon and Belmondo’s chemistry and the film’s stylistic bravado remain infectious, but its narrative hollows and Deray’s tepid direction reveal the chasm between ambition and execution. Like the fedoras it immortalised, the film is a stylish accessory—iconic in its moment, but destined to gather dust in the annals of cinema history.

RATING: 6/10 (++)

Blog in Croatian https://draxblog.com

Blog in English https://draxreview.wordpress.com/

InLeo blog https://inleo.io/@drax.leo

Hiveonboard: https://hiveonboard.com?ref=drax

InLeo: https://inleo.io/signup?referral=drax.leo

Rising Star game: https://www.risingstargame.com?referrer=drax

1Inch: https://1inch.exchange/#/r/0x83823d8CCB74F828148258BB4457642124b1328e

BTC donations: 1EWxiMiP6iiG9rger3NuUSd6HByaxQWafG

ETH donations: 0xB305F144323b99e6f8b1d66f5D7DE78B498C32A7

BCH donations: qpvxw0jax79lhmvlgcldkzpqanf03r9cjv8y6gtmk9

I love such movies