Film Review: Cabiria (1914)

Italian cinema has a long and distinguished history, including a relatively short period in the 1950s and 1960s when it was poised even to dethrone Hollywood as the global cinema leader. Its influence on the rest of the cinematic world is incalculable, contributing to the creation of many new styles, movements, and genres. One of the earliest examples is Cabiria, a 1914 silent film written and directed by Giovanni Pastrone, which is often considered to be the first true epic in the history of cinema.

The plot is loosely inspired by two novels—Salammbo by Gustave Flaubert and Carthage in Flames by Emilio Salgari—and takes place at the end of the 3rd Century BC, during the Second Punic War. The film is divided into five episodes, and the first begins in the Sicilian city of Catana, where wealthy Batto (played by Émile Vardannes) lives with his 8-year-old daughter Cabiria (played by Carolina Catena). When Etna erupts, a subsequent earthquake damages Batto’s villa, and some of his servants find a secret passage and take the opportunity to steal Batto’s treasure. One of them is Croessa (played by Gina Marangoni), who also takes young Cabiria with her. The fleeing servants, including Croessa and Cabiria, are captured by Phoenician pirates and sold as slaves in Carthage. There, Cabiria is selected by high priest Khartalo (played by Dante Testa) to be among a hundred children sacrificed to the god Moloch. She is saved from that fate by the timely arrival of Roman spy Fulvio Axilla (played by Umberto Mozzato) and his huge black servant Maciste (played by Bartolomeo Pagano). They manage to free her and leave her in the care of Sophonisba (played by Italia Almirante-Manzini), daughter of Carthaginian general Hasdrubal (played by Edoardo Davesnes). Maciste is, however, captured and spends the next ten years working as a slave. Fulvio Axilla, in the meantime, is an officer in the Roman fleet besieging Syracuse. When the fleet is destroyed by deadly “heat rays” invented by Archimedes (played by Enrico Gemmelli), Fulvio washes ashore and is brought to Batto’s house, where Batto learns that his daughter has come to Carthage. When Roman general Scipio Africanus (played by Luigi Chellini) invades North Africa, Fulvio seizes the opportunity to free Maciste and inquire about Cabiria’s fate. She is now known as “Elissa” (played by Lidia Quaranta), Sophonisba’s servant. Sophonisba, who loved pro-Roman Numidian king Massinissa (played by Vitale Di Stefano), is instead forced to marry Syphax (played by Alessandro Bernard), a pro-Carthaginian prince of Cirte, and Elissa/Cabiria finds herself in that city when it is besieged by Massinissa’s troops.

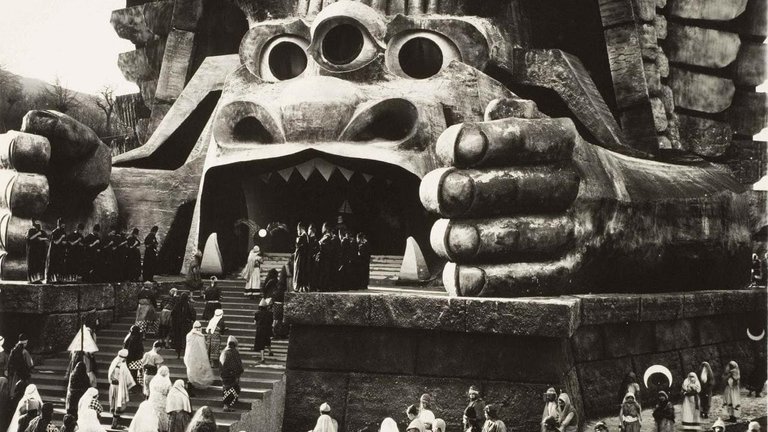

Like all major films of its period, Cabiria must be viewed by an audience aware of the technical limitations of its age. However, even with black-and-white cinematography and the lack of sound taken into consideration, Pastrone’s film doesn’t look like a groundbreaking technical achievement. Pastrone’s only innovation, which was later copied by many filmmakers, was the use of dolly shots, which were later nicknamed “Cabiria shots.” It is, however, used very sparingly in the film. Pastrone still prefers traditional static shots with very little editing. However, it is what Pastrone fills these shots with that makes Cabiria look impressive, even for viewers today. In an attempt to reconstruct the ancient past as accurately and spectacularly as possible, Cabiria features not only a large number of extras, plenty of exotic costumes, and large sets used for villas, palaces, temples, streets, and city walls. The latter, due to special effects being quite primitive, had to be replicated in their original size, and it can only be imagined how breathtaking it all looked to audiences more than a century ago. Furthermore, the lack of special effects and modern optical tricks meant that Pastrone had to rely on stunt work. The battle scene during the siege of Cirte, which features dozens of soldiers with ladders trying to storm the walls only to be tossed away to the ground, looks incredibly realistic and was probably an extremely dangerous part of production.

Pastrone’s skills as a screenwriter are evident here, although not particularly impressive. On one hand, he succeeds in connecting various characters and subplots into a coherent whole. On the other hand, some scenes, like Hannibal crossing the Alps (shot on actual Alpine locations with real-life elephants), serve little purpose apart from allowing Pastrone to show off. Famous Italian writer Gabriele d’Annunzio was supposed to write the screenplay, but in the end, he agreed only to provide text for intertitles. Most of the characters aren’t particularly memorable, including Cabiria, who appears as an adult relatively late in the film and is quite passive. That is, however, not the case with the heroic Fulvio Axilla and Maciste, who both function as early versions of action heroes. The latter, played by former Genoese dockworker Bartolomeo Pagano, establishes himself due to his impressive physique and ability to perform physically demanding and dangerous scenes. Unsurprisingly, Maciste became an icon of Italian silent cinema and later starred in 25 silent films; the character was reintroduced in the 1950s with many actors portraying him in various “sword and sandals” films.

Cabiria was, in many ways, a product of its time, with its content matching the national euphoria in Italy following a brief and successful war against the Ottoman Empire, during which the relatively freshly reunited country conquered Libya and began to reassert imperial glory for the first time since Roman times. Those sentiments, which would shortly after the premiere engulf Italy in the carnage of the First World War and later give birth to Fascism, are clearly present in the film, especially in the final scene where Fulvio and Cabiria triumphantly sail back from Africa. Some of today’s critics and scholars are likely to view Cabiria as nationalist and imperialist propaganda, and the disturbing scene of children being sacrificed in the temple of Moloch could easily be criticised as an attack on non-European civilisations based on not too credible ancient sources. However, the film was deeply appreciated and enjoyed even by non-Italian audiences while inspiring countless ambitious filmmakers around the world. One of those was D. W. Griffith, whose epic Intolerance—or, to be precise, its Babylon segment—is a clear and undoubtedly successful attempt to build upon what Pastrone started with Cabiria.

RATING: 7/10 (+++)

Blog in Croatian https://draxblog.com

Blog in English https://draxreview.wordpress.com/

Leofinance blog https://leofinance.io/@drax.leo

Unstoppable Domains: https://unstoppabledomains.com/?ref=3fc23fc42c1b417

Hiveonboard: https://hiveonboard.com?ref=drax

Bitcoin Lightning HIVE donations: https://v4v.app/v1/lnurlp/qrcode/drax

Rising Star game: https://www.risingstargame.com?referrer=drax

1Inch: https://1inch.exchange/#/r/0x83823d8CCB74F828148258BB4457642124b1328e

BTC donations: 1EWxiMiP6iiG9rger3NuUSd6HByaxQWafG

ETH donations: 0xB305F144323b99e6f8b1d66f5D7DE78B498C32A7

https://twitter.com/21393347/status/1642066752803569665

The rewards earned on this comment will go directly to the people( @drax ) sharing the post on Twitter as long as they are registered with @poshtoken. Sign up at https://hiveposh.com.