Film Review: Death in Venice (Morte a Venezia, 1971)

Certain films attain an almost cult-like devotion among cinephiles and film scholars, often being hailed as grand classics of cinema despite failing to live up to their reputations upon closer inspection. Death in Venice, Luchino Visconti’s 1971 period drama, epitomises this phenomenon. The film’s prestige is inextricably tied to its director’s legendary status and the bold subject matter of its source material—Thomas Mann’s 1912 novella—yet much of its acclaim feels overstated. While Visconti’s technical mastery and the film’s historical significance are undeniable, its narrative pacing, thematic ambiguity, and moral complexities often leave viewers underwhelmed, particularly when contrasted with the fervent reverence it garners in academic circles. The film’s status as a masterpiece seems more a product of its creator’s legacy and the era’s avant-garde sensibilities than of its inherent artistic or emotional merits.

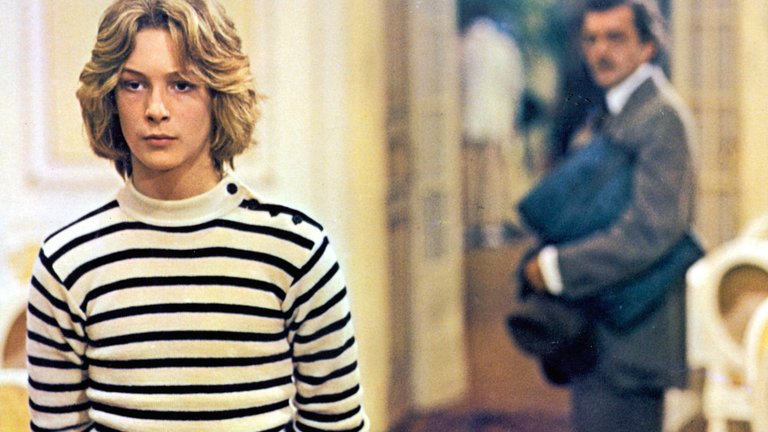

Adapted from Thomas Mann’s seminal novella Der Tod in Venedig, the film unfolds in early 1910s Venice, where German composer Gustav von Aschenbach (Dirk Bogarde) arrives seeking respite from professional stagnation and personal despair. His arrival coincides with the scirocco—a stifling southern wind that disrupts the city’s tranquillity and exacerbates tensions among its inhabitants. Settling at the Hotel Des Baines, Aschenbach encounters a Polish aristocratic family led by the unknown Polish aristocratic woman (Silvana Mangano) and her children, including the ethereal, androgynous teenage son Tadzio (Björn Andrésen). Aschenbach becomes increasingly fixated on Tadzio, obsessively observing him from afar while struggling to suppress his desire. Meanwhile, whispers of a cholera outbreak circulate, though the hotel manager (Romolo Valli) dismisses these concerns as routine summer precautions. The film’s tension escalates as Aschenbach’s obsession deepens, paralleling the mounting dread of the unseen epidemic—a metaphor for the moral decay festering beneath his disciplined exterior.

Visconti and co-writer Nicola Badalucco adhere closely to Mann’s novella, yet their deviations underscore the director’s personal stake in the material. Most significantly, they amplify the homoerotic undertones that Mann had delicately implied. Mann, who privately acknowledged his bisexuality but kept it hidden during his lifetime, framed Aschenbach’s infatuation with Tadzio as an aesthetic obsession rather than a sexual one. Visconti, however, capitalised on the Sexual Revolution’s ethos and his own openness about his homosexuality to make Aschenbach’s desires explicit. Scenes such as his visit to a brothel—a flashback featuring Carole Andre, future star of Sandokan, then an up-and-coming actress—underscore his inner conflict, while his jealousy over Tadzio’s interactions with another boy (Sergio Garfagnoli) and the barber’s (Franco Fabrizi) advice to “look younger” through cosmetics and hair dye, serve as overt symbols of his repressed identity. These choices transform the narrative from a metaphysical meditation into a visceral exploration of desire, though they risk reducing the complexity of Mann’s original psychological drama.

The film’s unapologetic portrayal of an older man’s fixation on a teenager has proven increasingly problematic over time. While Aschenbach never acts on his impulses, the mere framing of his obsession—particularly in scenes where he voyeuristically watches Tadzio play or sunbathe—invites accusations of normalising paedophilia. This discomfort is compounded by the casting of 15-year-old Björn Andrésen, whose androgynous beauty became central to the film’s aesthetic. Andrésen later revealed that Visconti pressured him into attending gay clubs against his will, blurring the line between artistic vision and exploitation. The 1971 documentary The Most Beautiful Boy in the World, which explores Andrésen’s life, further exposed the psychological toll of his role, painting the film as a relic of an era that prioritised art over ethical consideration. These revelations have eroded the film’s reputation, particularly among modern audiences who view its handling of underage characters as unconscionable.

Visconti’s decision to recast Aschenbach as a composer rather than the original writer reflects his fascination with the early 20th Century Austrian composer Gustav Mahler. Though prosthetics intended to make Bogarde resemble Mahler were discarded as impractical, Visconti paid homage through the film’s soundtrack, weaving Mahler’s symphonies into the narrative’s emotional core. The brooding opening sequence and the climactic death scene, underscored by Mahler’s Fifth Symphony, exemplify this fusion. This shift not only deepens the protagonist’s tragic arc—a creative genius undone by obsession—but also played a role in reviving Mahler’s popularity among classical music enthusiasts. However, the substitution occasionally feels forced, diluting the novella’s exploration of artistic integrity in literature for a more generic meditation on creativity.

Visconti and cinematographer Pasqualino De Santis transform Venice itself into a brooding, atmospheric protagonist. The film’s visuals—lavish close-ups of marble floors, gilded mirrors, and the labyrinthine canals—reflect the director’s meticulous attention to detail. De Santis’ lens captures the city’s duality: its beauty contrasts with the creeping dread of decay, symbolised by the scirocco’s oppressive heat and the sanitisation efforts meant to mask the cholera outbreak. The interplay of light and shadow, particularly in scenes where Tadzio bathes in sunlight, reinforces the tension between idealised beauty and moral corruption.

Bogarde delivers one of his most nuanced performances, embodying Aschenbach’s intellectual rigidity and crumbling self-control with chilling precision. His physical transformation—from a gaunt, disciplined composer to a dishevelled man consumed by obsession—is executed without melodrama, making his downfall palpably tragic. The actor’s ability to convey repressed longing through glances and strained gestures elevates the role into one of cinema’s most compelling studies of human frailty.

Despite its artistic merits, Death in Venice suffers from sluggish pacing that alienates modern audiences accustomed to tighter storytelling. Visconti’s insistence on lingering shots—such as the interminable sequences of Aschenbach staring at Tadzio—pads the runtime to over two hours, stretching the narrative into a drawn-out dirge. The film’s non-linear structure, including confusing flashbacks to Aschenbach’s conversations with his friend Alfred (Max Burns) about art, further obscures its themes. While these elements may have been intended to mirror the protagonist’s fragmented psyche, they often leave viewers disoriented rather than introspective. By the time Aschenbach collapses in the film’s final scene, many may feel relief at the film’s conclusion, underscoring its failure to sustain emotional engagement.

Death in Venice is a fascinating yet uneven work, a product of its era’s artistic daring and moral naivety. Visconti’s technical brilliance and Bogarde’s performance ensure its place in cinematic history, but its slow pacing, unresolved themes, and ethically dubious portrayal of paedophilic obsession render it a film better discussed than experienced. While its reputation as a classic is perpetuated by its director’s prestige and its influence on later homosexual-themed cinema, the viewing experience often feels like a relic of an older, less self-aware aesthetic. For all its beauty, Death in Venice ultimately serves as a reminder that art, however visionary, cannot always transcend the controversies and limitations of its own making.

RATING: 6/10 (++)

Blog in Croatian https://draxblog.com

Blog in English https://draxreview.wordpress.com/

InLeo blog https://inleo.io/@drax.leo

LeoDex: https://leodex.io/?ref=drax

Hiveonboard: https://hiveonboard.com?ref=drax

InLeo: https://inleo.io/signup?referral=drax.leo

Rising Star game: https://www.risingstargame.com?referrer=drax

1Inch: https://1inch.exchange/#/r/0x83823d8CCB74F828148258BB4457642124b1328e

BTC donations: 1EWxiMiP6iiG9rger3NuUSd6HByaxQWafG

ETH donations: 0xB305F144323b99e6f8b1d66f5D7DE78B498C32A7

BCH donations: qpvxw0jax79lhmvlgcldkzpqanf03r9cjv8y6gtmk9

It’s clear the film holds a special place because of its director and its literary depth but it struggles with style and storytelling and for me, it gets a bit boring.