Film Review: Easy Riders, Raging Bulls (2003)

The history of cinema would be incomplete without a number of seminal books that offer comprehensive overviews, serve as valuable sources, or provide critical reappraisals of its most fascinating chapters. One such volume, which may not be the definitive text but is certainly among the most controversial of recent decades, is Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls (1998). The book presents itself as an unofficial history of the New Hollywood era, became a bestseller, but also drew significant criticism for its alleged bias and reliance on salacious gossip. Its notoriety ensured it would be adapted, and five years later, Kenneth Bowser wrote and directed the feature-length documentary of the same name.

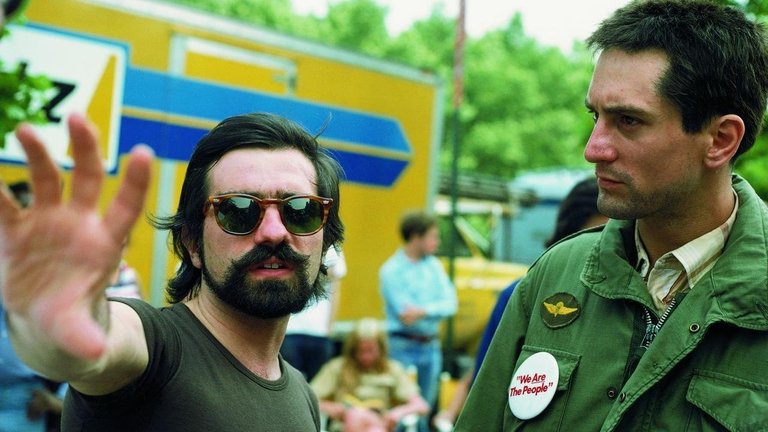

Bowser’s film, sometimes distributed under the subtitle How the Sex 'n' Drugs 'n' Rock 'n' Roll Generation Saved Hollywood, adopts a conventional chronological structure. It opens with a prologue set in 1966, illustrating the crumbling of the Classic Hollywood studio system and the rise of new creative forces. This void was filled by European cinema-inspired young filmmakers, B-movie producers like Roger Corman, and corporate outsiders like Charles Bludhorn, who installed the young Robert Evans at Paramount. The documentary then moves through the key milestones: the watershed success of Bonnie and Clyde (1967), the explosive year of 1969 with films like Easy Rider and Midnight Cowboy, and the early 1970s triumphs of Coppola’s The Godfather and Scorsese’s Mean Streets and Taxi Driver. It acknowledges the gathering of talent in Malibu and the pivotal shift represented by Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (1975) and George Lucas’s Star Wars (1977), which ushered in the blockbuster era. The narrative concludes with the movement’s decline, attributed heavily to personal excess and drug abuse, and posits Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull (1980) as its final masterpiece.

The film’s traditional approach—relying on stock footage, film clips, and present-day interviews—is competent but unsurprising. It will likely satisfy cinephiles and fans of the era, offering a visual companion to the period’s lore. However, its greatest weaknesses stem directly from its source material and the compromises of adaptation. A glaring issue is the absence of key figures. As noted, many of the primary subjects profiled in Biskind’s book, including Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Robert Altman, and William Friedkin, declined to participate in the documentary. This omission is telling. For Spielberg and Lucas, it can be traced to their harsh treatment in Biskind’s book, where they are portrayed as having “infantiliz[ed] the audience” and marched “backward through the looking glass,” effectively ending the New Hollywood ethos by returning to pre-1960s cinematic simplicities. Their commercial triumphs are framed within the documentary as the antithesis of the personal, director-driven cinema that defined the movement, but their voices are missing. Other major players like Francis Ford Coppola, who was highly critical of Biskind’s methods, are also absent. Consequently, the film relies on a chorus of supporting voices, which, while often insightful, creates a one-sided historical account.

This editorial imbalance exacerbates the documentary’s most significant failing: its superficial analysis of the New Hollywood collapse. The film leans heavily into a narrative of personal dissolution, where cocaine abuse and unchecked egos destroyed the creative community. While not without truth, this reduces a complex industrial and cultural shift to a moral fable. The documentary fails to adequately contrast the auteur-driven 1970s with the corporatised, franchise-focused model that Spielberg and Lucas’s films helped cement. The crucial context of rising marketing costs, the birth of the summer tentpole season, and the growing importance of overseas markets is largely missing.

Perhaps the most egregious omission is any substantive mention of the Heaven’s Gate disaster (1980). The catastrophic failure of Michael Cimino’s epic, which nearly bankrupted United Artists, is widely considered the death knell for director-controlled, big-budget projects within the studio system. Its absence is a staggering historical oversight. By choosing to end with Raging Bull, Bowser offers a more poetically satisfying, but less accurate, conclusion. The real end was not a critical triumph but a commercial catastrophe that made studios deeply risk-averse.

In compressing Biskind’s sprawling, gossip-laden book into a feature-length runtime, Bowser inevitably simplifies. What remains is a well-assembled, engaging retrospective that celebrates the era’s triumphs and laments its excesses. However, by both inheriting the book’s biases and failing to critically expand upon or challenge its theses, the documentary ultimately feels incomplete. It serves as a capable introduction but a flawed analysis, celebrating the sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll while glossing over the cold, hard business realities that truly killed the revolution.

RATING: 6/10 (++)

Blog in Croatian https://draxblog.com

Blog in English https://draxreview.wordpress.com/

InLeo blog https://inleo.io/@drax.leo

InLeo: https://inleo.io/signup?referral=drax.leo

Leodex: https://leodex.io/?ref=drax

Hiveonboard: https://hiveonboard.com?ref=drax

Rising Star game: https://www.risingstargame.com?referrer=drax

1Inch: https://1inch.exchange/#/r/0x83823d8CCB74F828148258BB4457642124b1328e

BTC donations: 1EWxiMiP6iiG9rger3NuUSd6HByaxQWafG

ETH donations: 0xB305F144323b99e6f8b1d66f5D7DE78B498C32A7

BCH donations: qpvxw0jax79lhmvlgcldkzpqanf03r9cjv8y6gtmk9