Film Review: Fist of Fury (1972)

Nationalism, as a force, has long occupied a paradoxical position in human history: it is both a unifying ideal and a catalyst for destruction. In its most fervent forms, it has ignited wars, justified colonial oppression, and fueled ideological extremism. Yet, curiously, this same force has also given rise to artistic and cultural movements that transcend national boundaries, resonating across continents and generations. The 1972 film Fist of Fury, directed by Lo Wei and starring Bruce Lee, stands as a striking example of this phenomenon. Officially the second film in Bruce Lee’s cinematic career, Fist of Fury did more than merely showcase its lead actor’s extraordinary martial arts prowess; it became a cultural touchstone, embodying Chinese nationalist sentiment while simultaneously achieving international acclaim. Its themes of resistance, vengeance, and national pride struck a chord with audiences worldwide, transforming it into a global sensation despite its deeply rooted cultural specificity.

The film’s origins lie in the historical legacy of Huo Yuanjia, a real-life martial arts master whose life and death became the subject of myth and controversy. A folk hero in early 20th-century China, Huo founded the Chin Woo Athletic Association, an institution that continues to hold prominence in martial arts circles today. His victories over foreign fighters, particularly in publicized bouts against Russian and Japanese opponents, were seen as symbolic triumphs for a China weakened by the decline of the Qing Dynasty and the encroachment of foreign powers. His untimely death in 1910, officially attributed to illness but widely suspected to be the result of poisoning by Japanese rivals, only deepened his legend. Fist of Fury takes these historical threads and weaves them into a fictionalised narrative, opening with a title card acknowledging that its plot is inspired by one of the many conspiracy theories surrounding Huo’s demise.

While Fist of Fury draws inspiration from the life of Huo Yuanjia, it departs significantly from historical accuracy in favour of dramatic storytelling. The film’s plot begins not with Huo himself, but with his fictional disciple, Chen Zhen, portrayed by Bruce Lee. Set in early 20th-century Shanghai, the film opens in the aftermath of Huo’s death, a moment of profound grief for the students of the Chin Woo Athletic Association. Though Huo is presented as a revered figure whose legacy looms over the story, his absence is keenly felt, and the film’s central conflict arises from the power vacuum left by his demise. This narrative shift allows the film to explore themes of loyalty, vengeance, and national identity through the lens of an individual rather than a historical icon.

Chen Zhen’s journey begins as he returns to Shanghai upon hearing news of his master’s death. His grief is palpable, but it is quickly overshadowed by outrage when he witnesses the mockery and humiliation inflicted upon Huo’s legacy by a rival Japanese martial arts school. Led by the Hiroshi Suzuki (Riki Hashimoto), this group of antagonists embodies the foreign oppression that looms over the Chinese characters throughout the film. Chen’s initial attempts to exercise restraint are repeatedly tested as a series of provocations culminate in violent confrontations. As he seeks answers about his master’s mysterious passing, he uncovers a conspiracy: Huo was poisoned by Tian (Huang Tsung-hsing), a Japanese spy who infiltrated the Chin Woo School under the guise of a humble cook. This revelation propels Chen into a path of vengeance, setting in motion a series of brutal showdowns that elevate the film from a mere martial arts spectacle to a deeply charged allegory of national resistance.

As Chen Zhen’s quest for justice unfolds, Fist of Fury transforms into a broader allegory of Chinese resistance against foreign domination. The film’s depiction of Shanghai, a city under the control of foreign powers through the International Settlement, serves as a potent backdrop for its themes of humiliation and defiance. The presence of Western and Japanese figures, often depicted as arrogant and condescending, reinforces the sense of national subjugation that fuels Chen’s crusade. This sentiment is most vividly captured in the infamous park scene, where Chen encounters a sign reading “Dogs and Chinese not allowed.” His explosive reaction—kicking the sign to pieces and engaging in a dramatic confrontation—serves as both a literal and symbolic rejection of foreign oppression. This sequence, though heavily dramatised, resonated deeply with audiences in postcolonial nations and among marginalised communities in the West, cementing the film’s status as an international phenomenon.

While the film’s nationalist fervour is undeniable, its narrative structure reveals a more complex, if somewhat contradictory, perspective on resistance. Chen’s unwavering commitment to vengeance sets him at odds with the more pragmatic approach of his fellow Chin Woo students, who seek to preserve their school through diplomacy rather than violence. This tension reflects a broader historical dilemma: whether to resist oppression through direct confrontation or through endurance and adaptation. However, the film ultimately negates any middle ground, as both approaches lead to bloodshed and tragedy. In the climactic finale, Chen emerges victorious in a brutal duel against Suzuki and his Russian ally Petrov, only to return to the Chin Woo School and discover that most of his comrades have been massacred. In a final act of defiance, he surrenders himself to the International Settlement police, culminating in the famous “Bolivian Army” ending where he is gunned down in a hail of bullets. This bleak conclusion, underscores the film’s underlying fatalism. Resistance, the film suggests, may be noble, but it is also fraught with peril and often futile.

From a technical standpoint, Fist of Fury marked a noticeable evolution in Bruce Lee’s cinematic trajectory. Released mere months after his breakthrough role in The Big Boss (1971), the film demonstrated a more refined and deliberate approach to martial arts choreography and storytelling. Unlike the relatively straightforward action sequences of The Big Boss, which leaned heavily on Lee’s raw physicality and efficiency in dispatching adversaries, Fist of Fury embraced a more stylized and symbolic approach. The studio-bound production allowed for greater control over set design and lighting, lending the film a more polished aesthetic. However, this controlled environment also introduced some anachronistic elements—costumes, hairstyles, and props occasionally clashed with the film’s early 20th-century setting. A particularly jarring example is the character of Petrov, the Russian strongman and Suzuki’s ally, portrayed by Bruce Lee’s American student Robert Baker. His modern, almost contemporary appearance contrasts starkly with the historical backdrop, momentarily disrupting the film’s immersion.

Despite these inconsistencies, the film’s visual and choreographic choices contributed significantly to its lasting impact. The fight sequences, particularly the climactic duel between Chen Zhen and Suzuki, were meticulously staged to emphasize not just physical prowess but also ideological confrontation. The use of slow-motion cinematography during key strikes and the rhythmic pacing of combat exchanges elevated martial arts beyond mere spectacle, infusing it with a sense of poetic justice. While Fist of Fury may not have been historically accurate in its details, its stylistic choices and thematic ambitions positioned it as a more ambitious work than its predecessor, cementing Bruce Lee’s status as a cinematic force and martial arts legend.

Despite its technical advancements and thematic boldness, Fist of Fury is not without its narrative inconsistencies and tonal dissonance. One of the film’s most glaring weaknesses lies in the one-dimensionality of Bruce Lee’s protagonist, Chen Zhen. While his martial prowess is undeniably captivating, his character is largely defined by a singular, unrelenting rage that leaves little room for nuance. This is most starkly evident in the film’s attempt at emotional depth, particularly in the scene where Chen collapses at Huo Yuanjia’s funeral, wailing in grief until he must be forcibly restrained. The moment, intended to convey profound loss, instead veers into melodrama, its exaggerated pathos bordering on unintentuonal parody. This tendency towards heightened emotion is further exacerbated by the inclusion of a perfunctory romantic subplot involving Chen’s fiancée, played by Nora Miao. Their interactions, sparse and awkwardly inserted into the narrative, serve little purpose beyond fulfilling a conventional expectation of the genre, offering neither meaningful character development nor thematic resonance.

Compounding these issues is the film’s uneasy balancing act between ideological messaging and commercial appeal. Scenes of explicit sexualization, such as the stripper sequence featuring Suzuki and Petrov in a moment of decadent revelry, feel particularly jarring within the broader context of the film’s nationalist rhetoric. This dissonance suggests a tension between Lo Wei’s directorial instincts and Bruce Lee’s artistic vision, with the former seemingly prioritizing exploitative spectacle while the latter sought to elevate martial arts cinema into something more profound. Similarly, the presence of female students at the Chin Woo School, an anachronistic nod to the progressive ideals of the early 1970s, feels like an artificial concession rather than a natural evolution of the narrative. While well-intentioned, these elements highlight the film’s struggle to reconcile its political aspirations with the commercial realities of the martial arts genre.

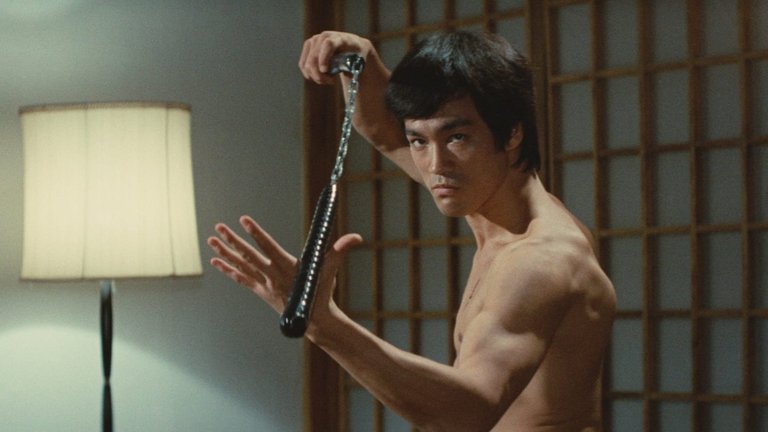

Despite its narrative shortcomings, Fist of Fury remains an enduring testament to Bruce Lee’s unparalleled charisma and martial arts mastery. While the film’s plot is often secondary to its action sequences, it is precisely these sequences that elevate the film beyond a mere genre exercise. Lee’s performances in Fist of Fury—particularly his climactic duel against Riki Hashimoto’s Suzuki and his showdown with Robert Baker’s Petrov—are masterclasses in precision, rhythm, and physical storytelling. Unlike the more straightforward brawls of The Big Boss, the fights in Fist of Fury are imbued with a heightened sense of symbolic confrontation, with each movement carrying the weight of national pride and personal vengeance. The iconic use of nunchaku, introduced in this film and later emulated in countless martial arts movies, became an enduring symbol of Lee’s influence on global cinema. His ability to blend speed, power, and theatricality in each frame not only showcased his physical abilities but also reinforced his status as a cinematic icon.

The film’s success was both immediate and far-reaching, cementing Bruce Lee’s status as an international superstar and reshaping the landscape of Hong Kong cinema. Its appeal extended well beyond Chinese audiences, resonating with viewers in the West and throughout the Third World, where its themes of resistance and defiance against oppression struck a chord. The commercial triumph of Fist of Fury also paved the way for a wave of imitations, as studios sought to replicate Lee’s success with a slew of “Bruceploitation” films—low-budget martial arts features that often cast lookalikes or actors who had trained with Lee. The most notable of these was Lo Wei’s New Fist of Fury (1976), which, despite being a transparent attempt to cash in on Lee’s legacy, played a crucial role in launching the career of another martial arts legend, Jackie Chan. This posthumous influence underscores the enduring impact of Fist of Fury and Bruce Lee’s transformative role in shaping global action cinema.

RATING: 7/10 (+++)

Blog in Croatian https://draxblog.com

Blog in English https://draxreview.wordpress.com/

InLeo blog https://inleo.io/@drax.leo

Hiveonboard: https://hiveonboard.com?ref=drax

InLeo: https://inleo.io/signup?referral=drax.leo

Rising Star game: https://www.risingstargame.com?referrer=drax

1Inch: https://1inch.exchange/#/r/0x83823d8CCB74F828148258BB4457642124b1328e

BTC donations: 1EWxiMiP6iiG9rger3NuUSd6HByaxQWafG

ETH donations: 0xB305F144323b99e6f8b1d66f5D7DE78B498C32A7

BCH donations: qpvxw0jax79lhmvlgcldkzpqanf03r9cjv8y6gtmk9