A 103 años del natalicio de Eric Rohmer / 103 years since Eric Rohmer's birth (ESP/ENG)

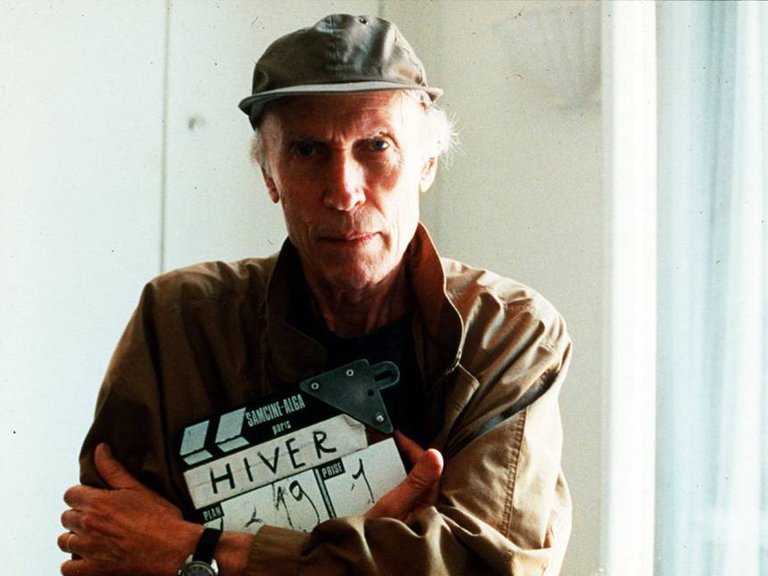

Este año se conmemoran los 103 años del nacimiento del profesor, guionista, novelista, periodista, critico cinematográfico y director de cine francés Jean Marie Maurice Schérer o Maurice Henri Joseph Schérer, mejor conocido como Eric Rohmer, figura intelectual importante de la llamada Nouvelle vague (Nueva Ola) francesa y editor de la prestigiosa revista de cine Cahiers du Cinéma.

Nacido en 1920, sin nunca haber sido muy claro sobre sus datos de origen o su verdadero nombre, Rohmer es reconocido por varias obras cinematográficas influyentes que cimentaron una estética que enfatizaba la importancia del dialogo como artificio argumental, la elegancia formal naturalista y la narración sutil, enfocada en la exploración de la psicología y las relaciones humanas.

Entre sus películas más notables, y especialmente recomendadas, están "Mi noche con Maud" (1969), "Cuento de verano" (1996), "La rodilla de Clara" (1970), "Pauline en la playa" (1983), "La mujer del aviador" (1981), y “El rayo verde” (1986).

Durante su trayectoria obtuvo cuarenta nominaciones a distintos premios y festivales alrededor del mundo, que incluyen la Concha de Oro del Festival de San Sebastián, el León de Oro de Venecia, el Premio Luchino Visconti, el Premio FIPRESCI y el Oso de Oro de Berlín.

De la literatura al cine

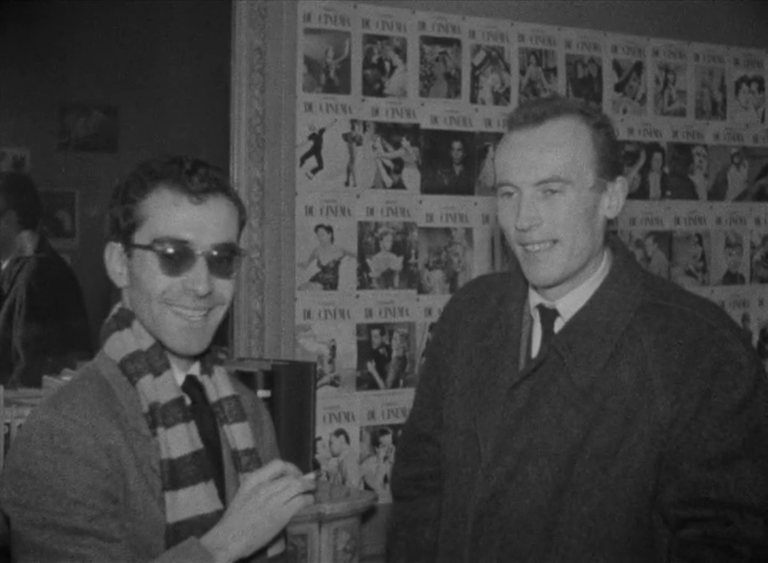

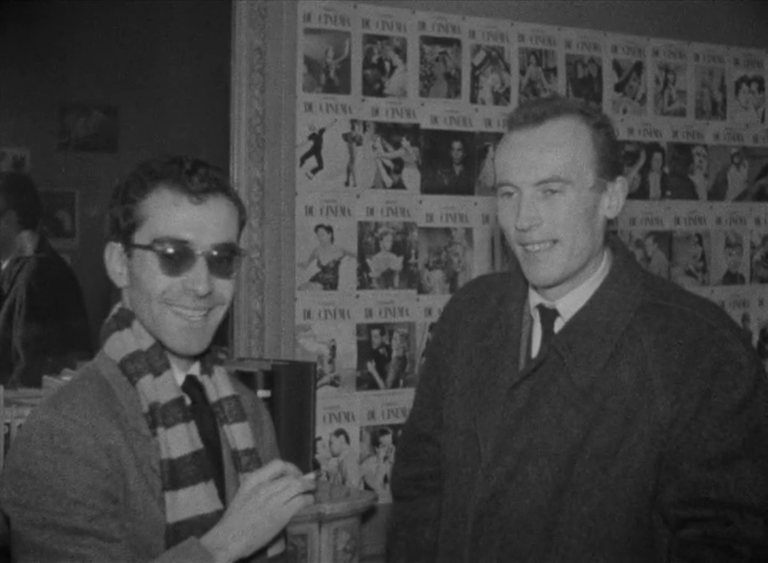

Antes más inclinado por la literatura, su interés por el cine nació al comenzar a asistir a proyecciones en la Cinemateca Francesa de Henri Langlois en los años 40, donde conoció y forjo amistad con Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, y Jacques Rivette, futuros compañeros de movimiento quienes se harían un nombre propio en la cinematografía mundial.

A partir de allí, cambio la literatura por el cine adoptando el seudónimo de Eric Rohmer, sacado de la combinación de los nombres del actor y director de cine en la era silente Erich Von Stromhein y del escritor de la novela serial Fu Manchu, Sax Rohmer.

Luego de abandonar el periodismo por la crítica cinematográfica, en 1949 comienza a escribir reseñas en las revistas Révue du Cinéma, Arts, Temps Modernes y La Parisienne, y en 1950 co-funda la efímera revista La Gazette du Cinéma junto a Rivette y Godard.

Ya en 1951 Rohmer ingresa a la recientemente inaugurada Cahiers du Cinéma de André Bazin, donde desarrolló un estilo distintivo, retorico e impersonal que lo distinguió entre sus compañeros, para después ascender al puesto de jefe de redacción de la publicación en 1956.

Sus películas: las tres sagas más reconocidas

En el desarrollo de su carrera como director, Rohmer se caracterizó por hacer películas de distinta índole que combinaban tramas sencillas con agudeza intelectual. Pero para quien quiera conocer su cine, lo mejor sería comenzar por sus tres grandes etapas temáticas que se extendieron desde los incipientes 60 hasta finales de los 90.

Luego de sus primeros intentos de dirigir en los años 50, no fue hasta 1963 cuando comienza con su primera saga denominada “Seis cuentos morales”, los cuales habían sido originalmente concebidos como una novela.

Cada película de este primer ciclo sigue una misma premisa, inspirada en “Amanecer: Una canción de dos humanos” (1927) de F. W. Murnau: un hombre, casado o quizás comprometido con una mujer, es tentado por una segunda, pero finalmente vuelve con la primera.

Estos seis cuentos morales constan de cortos y largometrajes que incluyen “La panadera de Monceau” (1963), “La carrera de Suzanne” (1963), “La coleccionista” (1967), “Mi noche con Maud” (1969), “La rodilla de Clara” (1970), y “El amor después del mediodía” (1972).

Posteriormente de hacer otros proyectos menos personales durante el resto de la década de los 70s, Rohmer se embarca en una segunda saga llamada "Comedias y proverbios", con la idea de que cada película se base en un proverbio o dicho popular.

Allí se cuentan “La mujer del aviador” (1981), “La buena boda” (1982), “Pauline en la playa” (1983), “Las noches de la luna llena” (1984), “El rayo verde” (1986), y “El amigo de mi amiga” (1987).

Su tercera y última saga la realizó en la década de 1990 con los “Cuentos de las cuatro estaciones”. En esta ocasión realizó cuatro títulos: “Cuento de primavera” (1990), “Cuento de verano” (1996), “Cuento de otoño” (1998), y “Cuento de invierno” (1992).

Ya en el nuevo milenio realizó otras tres películas de época, muy dispares entre si, hasta que en 2007 anuncio su retiro formal del medio.

Estilo e influencia en la escena mundial

Eric Rohmer fue uno de los directores de cine más importantes de la década de 1960 y su contribución al cine independiente y al movimiento de la Nouvelle Vague es innegable. Su estilo, centrado en protagonistas inteligentes y elocuentes que a menudo no son capaces de reconocer sus deseos, hacen del contraste entre lo que dicen y lo que hacen, una pieza fundamental que alimenta gran parte del dramatismo de sus películas.

Existen muchas opiniones de críticos y cineastas sobre Eric Rohmer y su obra. Algunos lo consideran uno de los directores más importantes de la Nouvelle Vague y un gran escritor de diálogos, mientras que otros pueden encontrar su estilo naturalista demasiado lento o falto de acción.

Quentin Tarantino, Richard Linklater, Wes Anderson, Olivier Assayas, y Noah Baumbach son algunos de los cineastas contemporáneos que comparten admiración por Rohmer en su enfoque de la narración, los diálogos, y en la exploración de la psicología y las complejidades de las relaciones humanas.

Tarantino ha mencionado a Rohmer como una influencia en su trabajo de diálogos, citando "Mi noche con Maud" como una de las razones de su amor por el cine, mientras que el director de cine francés Olivier Assayas ha elogiado a Rohmer por su habilidad para capturar la naturaleza humana y el desarrollo narrativo con un sentido cinematográfico impecable.

Anne-Laure Meury en La mujer del aviador

Por su parte, Richard Linklater lo ha citado como una influencia en su trabajo, y ha mencionado su admiración por la forma en que maneja los diálogos y la naturalidad en sus películas, tanto así que su trilogía del “Antes” viene directamente tocada por “La mujer del aviador”.

En general, Rohmer ha sido y sigue siendo considerado una figura importante en la historia del cine y hasta el día de hoy continúa inspirando y fascinando por igual a cineastas, críticos y espectadores en todo el mundo.

¿Por qué ver las películas de Rohmer?

Ver escenas y diálogos largos sin mucha “acción” para comprender los valores de los personajes no es tarea fácil. Bien lo decía también Quentin Tarantino en una entrevista donde señalaba que el cine de Rohmer no era para todo el mundo.

"Tienes que ver una, y si te gusta esa, entonces deberías ver las otras, pero tienes que ver una para ver si te gusta", dijo.

Es que estas películas contienen una serie de claves que no se encuentran fácilmente en el cine actual. Allí, los personajes tienen un propósito y defienden principios que acaban siendo cuestionados, lo que genera un conflicto interno que instiga la autorreflexión en quien las ve, retando al espectador y haciendo que el público piense de manera crítica.

Por eso, el poeta, ensayista y crítico cinematográfico Gerard Legrand dijo alguna vez que (Rohmer) "es uno de los pocos cineastas que invita constantemente a ser inteligente, más inteligente que sus (simpáticos) personajes".

Eso, por sí solo, resulta extraordinario.

This year marks the 103rd anniversary of the birth of French professor, screenwriter, novelist, journalist, film critic and film director Jean Marie Maurice Schérer or Maurice Henri Joseph Schérer, better known as Eric Rohmer, an important intellectual figure of the so-called French Nouvelle vague (New Wave) and editor of the prestigious film magazine Cahiers du Cinéma.

Born in 1920, without ever being very clear about his origins or his real name, Rohmer is recognized for several influential cinematic works that cemented an aesthetic that emphasized the importance of dialogue as plot device, naturalistic formal elegance and subtle storytelling, focused on the exploration of psychology and human relationships.

Among his most notable and especially recommended films are "My Night at Maud's " (1969), "A Summer's tale" (1996), "Clara's Knee" (1970), "Pauline at the Beach" (1983), "The Aviator's Wife" (1981), and "The Green Ray" (1986).

During his career he received forty nominations for different awards and festivals around the world, including the Golden Shell at the San Sebastian Festival, the Golden Lion at Venice, the Luchino Visconti Award, the FIPRESCI Award and the Golden Bear at Berlin.

From literature to cinema

Previously more inclined to literature, his interest in cinema was born when he began attending screenings at Henri Langlois' Cinémathèque Française in the 1940s, where he met and befriended Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, and Jacques Rivette, future companions in the movement who would make a name for themselves in world cinema.

From then on, he switched from literature to cinema, adopting the pseudonym Eric Rohmer, taken from the combination of the names of the silent era actor and film director Erich Von Stromhein and Sax Rohmer, the writer of the serial novel Fu Manchu.

After abandoning journalism for film criticism, in 1949 he began writing reviews for the magazines Révue du Cinéma, Arts, Temps Modernes and La Parisienne, and in 1950 he co-founded the short-lived magazine La Gazette du Cinéma with Rivette and Godard.

In 1951 Rohmer joined André Bazin's recently inaugurated Cahiers du Cinéma, where he developed a distinctive, rhetorical and impersonal style that distinguished him among his peers, and was later promoted to the position of editor-in-chief of the publication in 1956.

His films: the three most renowned sagas

In the development of his career as a director, Rohmer was characterized by making films of different kinds that combined simple plots with intellectual acuity. But for those who want to get to know his cinema, it would be best to start with his three great thematic stages that extended from the incipient 60s to the end of the 90s.

After his first attempts at directing in the 1950s, it was not until 1963 that he began his first saga called "Six Moral Tales", which had originally been conceived as a novel.

Each film in the cycle follows the same premise, inspired by F. W. Murnau's "Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans" (1927): a man, married or perhaps engaged to one woman, is tempted by a second, but eventually returns to the first.

These six moral tales consist of short and feature-length films including "The Baker of Monceau" (1963), "Suzanne's Career" (1963), "The Collector" (1967), "My Night at Maud's " (1969), "Clara's Knee" (1970), and "Love in the Afternoon" (1972).

After making other less personal projects during the rest of the 1970s, Rohmer embarked on a second saga called "Comedies and Proverbs", with the idea that each film would be based on a popular proverb or saying.

These include "The Aviator's Wife" (1981), "Le Beau Mariage" (1982), "Pauline at the Beach" (1983), "Full Moon in Paris" (1984), "The Green Ray" (1986), and "Boyfriends and Girlfriends" (1987).

His third and last saga was made in the 1990s with the “Tales of the Four Seasons”. On this occasion he produced four titles: "A Tale of springtime" (1990), "A Summer's tale" (1996), "Autumn tale" (1998), and "A Tale of winter" (1992).

In the new millennium he made three other very different period films, until 2007, when he announced his formal retirement from the medium.

Style and influence on the world scene

Eric Rohmer was one of the most important film directors of the 1960s and his contribution to independent cinema and the Nouvelle Vague movement is undeniable. His style, centered on intelligent and eloquent protagonists who are often unable to recognize their desires, makes the contrast between what they say and what they do, a fundamental piece that feeds much of the drama of his films.

There are many opinions of critics and filmmakers about Eric Rohmer and his work. Some consider him one of the most important directors of the Nouvelle Vague and a great dialogue writer, while others may find his naturalistic style too slow or lacking in action.

Quentin Tarantino, Richard Linklater, Wes Anderson, Olivier Assayas, and Noah Baumbach are some of the contemporary filmmakers who share admiration for Rohmer in his approach to storytelling, dialogue, and in exploring the psychology and complexities of human relationships.

Tarantino has cited Rohmer as an influence on his dialogue work, citing "My Night at Maud's" as one of the reasons for his love of film, while French filmmaker Olivier Assayas has praised Rohmer for his ability to capture human nature and narrative development with impeccable cinematic sense.

Anne-Laure Meury in The Aviator's Wife

For his part, Richard Linklater has cited him as an influence on his work, and has mentioned in several interviews his admiration for the way he handles dialogue and naturalness in his films, so much so that his "Before" trilogy comes directly touched by "The Aviator's Wife."

Overall, Rohmer has been and still is considered an important figure in the history of cinema and to this day continues to inspire and fascinate filmmakers, critics and viewers alike around the world.

Why watch Rohmer's films?

Watching long scenes and dialogues without much "action" to understand the values of the characters is not an easy task. Quentin Tarantino also said it well in an interview where he pointed out that Rohmer's cinema was not for everyone.

"You have to see one of [Rohmer's movies], and if you kind of like that one, then you should see his other ones, but you need to see one to see if you like it," he said.

It's that these films contain a number of cues not easily found in today's cinema. There, the characters have a purpose and defend principles that end up being questioned, which generates an internal conflict that instigates self-reflection in the viewer, challenging them and making the audience think critically.

That is why the poet, essayist and film critic Gerard Legrand once said that he (Rohmer) "is one of the rare filmmakers who is constantly inviting you to be intelligent, indeed, more intelligent than his (likable) characters."

That alone is remarkable.

0

0

0.000

0 comments