Has Monty Python lost its humor or have we lost our humor? // Monty Python perdeu a graça ou foi nós que perdemos o humor?

The thing about forcing yourself to watch a comedy classic-and here, by "classic", I mean something that an entire generation, specifically our parents' generation (but not every parent, I see many who didn't laugh at Python 18 years ago when I discovered the movies and who still don't laugh today), the one that wore bell-bottoms without irony, has repeatedly assured us is the pinnacle of Intelligent Satire-is that the experience comes pre-loaded with a layer of performance anxiety. The spectator's performance. You're sitting there, on the sofa that already has the mold of your body in the foam oppressed by the weight, with the bluish glow of the TV screen and because you can't find any streaming that has exhumed this relic from 1979, you end up downloading it pirated via torrent (like in the good years of 2005) and you feel the weight not only of the film itself, but of the cultural expectation that envelops it like a shroud. When I saw it for the first time back then, there was a pressure for it to be a comedy about intelligent people, it was the dawn of sarcasm, of acidity, but today it sounds like naive acting in many moments. Back then I laughed because I really liked it, I think in my young mind it was so humorless and caustic (for the time) that it sounded incredible. But now here, in the present moment, I was facing immense pressure caused only by myself: The pressure to enjoy. And, above all, the overwhelming pressure to laugh. Laugh in the right way. That laugh that is both intelligent and visceral, the laugh that says: "Oh yes, I caught the reference to the sectarianism of the British left in the 1970s AND I also found the penis of a Roman with a funny name inherently hilarious".

Monty Python's Life of Brian comes to me, a 37-year-old Millennial, not as a movie, but as homework. A cultural artifact whose fame precedes it in such a way that watching it for the first time in, say, 2025, is less an act of re-analysis and more one of socio-cultural archaeology (which, damn it! Just by going down that road, the movie already becomes boring, I wonder how many comedy movies I loved, spoiler: Dude, Where's My Car; Who's Gonna Get Mary; Superbad; Pineapple Express; Scary Movie, etc., would survive today's serious, sad and inherently NATURAL moment. Anyway, I dug up something with my girlfriend that had the look of gold from a bygone era, but which, under the cold, relentless light of our 4K screens, looks like... something else. something else. A different metal, perhaps. Brass, possibly. Brass that has been polished so vigorously by decades of acclaim that its shine now looks more like the sweat of effort than genuine brilliance. And herein lies perhaps the uncomfortable crux of the matter, the kind of truth you hesitate to admit at a dinner party with older, more culturally secure people: for the most part, The Life of Brian isn't funny. Not in a way that produces that involuntary, gasping laughter that is the true mark of great humor. Instead, it elicits, at best, an appreciative nod. "Ah, I see what they did there. Cunning." And at worst, and with alarming frequency, it provokes a very specific kind of generational discomfort, a sensation that contemporary language, in its glorious lack of subtlety, has labeled cringe, a term that defines very well everything that England has tried to do in cinematic humor 90% of the time. It's a discomfort that manifests itself physically: a slight frown, an almost imperceptible shrug of the shoulders, the sudden desire to check cell phone notifications.

Monty Python's Life of Brian comes to me, a 37-year-old Millennial, not as a movie, but as homework. A cultural artifact whose fame precedes it in such a way that watching it for the first time in, say, 2025, is less an act of re-analysis and more one of socio-cultural archaeology (which, damn it! Just by going down that road, the movie already becomes boring, I wonder how many comedy movies I loved, spoiler: Dude, Where's My Car; Who's Gonna Get Mary; Superbad; Pineapple Express; Scary Movie, etc., would survive today's serious, sad and inherently NATURAL moment. Anyway, I dug up something with my girlfriend that had the look of gold from a bygone era, but which, under the cold, relentless light of our 4K screens, looks like... something else. something else. A different metal, perhaps. Brass, possibly. Brass that has been polished so vigorously by decades of acclaim that its shine now looks more like the sweat of effort than genuine brilliance. And herein lies perhaps the uncomfortable crux of the matter, the kind of truth you hesitate to admit at a dinner party with older, more culturally secure people: for the most part, The Life of Brian isn't funny. Not in a way that produces that involuntary, gasping laughter that is the true mark of great humor. Instead, it elicits, at best, an appreciative nod. "Ah, I see what they did there. Cunning." And at worst, and with alarming frequency, it provokes a very specific kind of generational discomfort, a sensation that contemporary language, in its glorious lack of subtlety, has labeled cringe, a term that defines very well everything that England has tried to do in cinematic humor 90% of the time. It's a discomfort that manifests itself physically: a slight frown, an almost imperceptible shrug of the shoulders, the sudden desire to check cell phone notifications.

Let me be brutally honest for a second. The movie's central joke, the one that gives it its narrative backbone, is a sitcom premise, not a bad one. A case of mistaken identity. Brian Cohen, a perfectly ordinary man, born in the manger next door, is mistaken for the Messiah. It's a brilliant idea. It's the kind of idea that, if you had it, you'd rush to write it down in a notebook that you'll never remember to revisit, but at least you made sure you wrote it down. The problem isn't with the concept. The problem, for the contemporary viewer, lies in the incessant, almost frenetic execution of everything that surrounds it. Python humor, at least in its cinematic incarnation, operates at a consistently blistering volume. It's physical, performative humor. It's theatrical, full of grimaces and squeaky voices. Now at a distance of almost fifty years, my comment might have been a hesitant, "Well, yes, you're clever, I guess, but could you please keep it down a bit?". There's an almost desperate quality to the way many jokes are hammered out, as if the mere repetition of a silly concept (the name "Biggus Dickus", the debate about what the Romans gave us, the split between the Popular Front of Judea and the Jewish People's Front) were enough to turn it into a masterpiece of humor.

For a generation raised on a diet of humor that often relies on the subtext, unconscious dadaism, multi-layered irony and social discomfort of The Office (American, because let's face it, the original British Office is AWFUL) or the surreal and melancholic deconstruction of BoJack Horseman, this brute force approach (or late-boomer humor) seems... strange. strange. Old-fashioned. Language has changed. Not the spoken language, but the semiotic language of comedy. What was once a cutting satire on the futility of left-wing sectarianism now seems like a tediously accurate representation of an average day on Twitter. Parody has been overtaken by reality to the point where it no longer reflects or exaggerates the world; it merely describes it, but with British accents of men doing women's voices. And the shock of recognition is no longer funny; it's simply tiresome. And then, of course, we come to the question of Blasphemy. With a capital B. The original controversy that cemented the film's legendary status. Banned in Norway, denounced by religious groups, seen as a courageous and unprecedented attack on organized Christianity. In 1979, that was dynamite. It was an act of genuine transgression, a punch up against a monolithic and powerful institution. Watching it today, through the eyes of an atheist living in a largely secularized Western society, where criticism of organized religion is commonplace on podcasts, stand-up specials and internet forums, the impact of the film's blasphemy seems incredibly... mild.

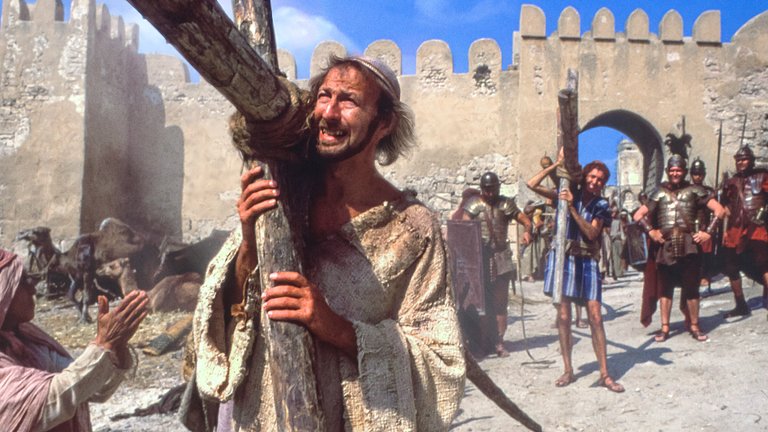

Which brings us, in a circuitous and perhaps unnecessarily complicated way, to the scene that has perhaps aged the most uncomfortably of all. The scene in which Stan, played by Eric Idle, announces his desire to be a woman called Loretta and to have the right to have babies. John Cleese's reaction as Reg is one of logical exasperation. "But you can't have babies... you don't have a uterus!" is presented as the height of satire on identity politics taken to an illogical extreme. This sense of temporal mismatch permeates everything. The visual jokes, such as the chase with the aliens, seem inserted from another movie, a random sketch that breaks whatever diegetic rhythm the narrative was trying to build. The aesthetic itself, with its Judean brown and beige color palette filmed in Tunisia, although authentic, contributes to a sense of distance, of dryness. It's a film that you admire more than you like, after all, in those years the actors acted, ran, moved, the sets were real, there was detailed scenography, a lot of manpower, work force for the sake of a work, all of which now seems almost like a movie museum (I wonder what it would be like to watch a Ben-Hur of the time). The climax, the famous crucifixion scene with the song "Always Look on the Bright Side of Life", is perhaps the moment when the film comes closest to achieving the transcendence it's been given. It's a brilliant juxtaposition of horror and joy, a hymn to stoicism in the face of annihilation. Blah blah blah, but at the same time maybe my hanedonia and end-of-movie sleepiness took away any sincere charm, it seems they always slipped before reaching the climax of the jokes.

In short, the experience of watching The Life of Brian was like visiting a childhood home that has been sold to new owners. The structure is still there. You recognize the architecture. You can see where things used to be. But the furniture is all different, there's a strange smell in the air and you feel like an intruder. The film became a monument to a specific type of humor - a Cambridge-educated white-collar humor that revelled in its own intelligence and used absurdity as a weapon against the establishment. The Pythons were, in fact, Boomers way ahead of their time. So far ahead, perhaps, that they arrived in a future we now inhabit, but didn't foresee that, by the time we arrived, we would have heard all their jokes before, told in different ways, in different contexts, by people who saw what they did and built on it, or simply saw reality become stranger than any parody they could conceive. There is no joy in declaring a classic to be dated. It feels like sacrilege, a failure on the part of the viewer. "Maybe the problem is me," I thought. "Maybe I'm not smart enough anymore. Maybe I've been hopelessly corrupted by the internet." And maybe there's a bit of truth in that. But perhaps the greater truth is that comedy, more than any other art form, is perishable and ages like milk. It depends on a tacit contract with its audience, a shared set of norms, anxieties and targets. When that contract expires, what remains is no longer a living joke, but the ghost of one. And The Life of Brian, with all its undeniable brilliance and historical importance, now seems haunted by these ghosts. We laughed, when we laughed, not at the film itself, but at the echo of a laugh from almost half a century ago, a laugh that we can recognize, admire, but which, to our frustration and perhaps a little sadness, we simply can no longer feel as our own. In the end, it was good to see it to know that it's not as good as it once was.

In short, the experience of watching The Life of Brian was like visiting a childhood home that has been sold to new owners. The structure is still there. You recognize the architecture. You can see where things used to be. But the furniture is all different, there's a strange smell in the air and you feel like an intruder. The film became a monument to a specific type of humor - a Cambridge-educated white-collar humor that revelled in its own intelligence and used absurdity as a weapon against the establishment. The Pythons were, in fact, Boomers way ahead of their time. So far ahead, perhaps, that they arrived in a future we now inhabit, but didn't foresee that, by the time we arrived, we would have heard all their jokes before, told in different ways, in different contexts, by people who saw what they did and built on it, or simply saw reality become stranger than any parody they could conceive. There is no joy in declaring a classic to be dated. It feels like sacrilege, a failure on the part of the viewer. "Maybe the problem is me," I thought. "Maybe I'm not smart enough anymore. Maybe I've been hopelessly corrupted by the internet." And maybe there's a bit of truth in that. But perhaps the greater truth is that comedy, more than any other art form, is perishable and ages like milk. It depends on a tacit contract with its audience, a shared set of norms, anxieties and targets. When that contract expires, what remains is no longer a living joke, but the ghost of one. And The Life of Brian, with all its undeniable brilliance and historical importance, now seems haunted by these ghosts. We laughed, when we laughed, not at the film itself, but at the echo of a laugh from almost half a century ago, a laugh that we can recognize, admire, but which, to our frustration and perhaps a little sadness, we simply can no longer feel as our own. In the end, it was good to see it to know that it's not as good as it once was.

Rate: 3/10

Thanks for reading!

Thomas Blum

Português

A coisa sobre se forçar a assistir a um clássico da comédia—e aqui, por “clássico”, quero dizer algo que uma geração inteira, especificamente a geração de nossos pais (mas não todo pai, vejo muitos que não riram com Python há 18 anos quando descobri os filmes e que continuam não rindo até hoje), aquela que usava calças boca de sino sem ironia, nos assegurou repetidamente que é o ápice da Sátira Inteligente—é que a experiência vem pré-carregada com uma camada de ansiedade de desempenho. O desempenho do espectador. Você está sentado ali, no sofá que já tem o molde do seu corpo na espuma oprimida pelo peso, com o brilho azulado da tela de TV e por não encontrar nenhum streaming que tenha exumado esta relíquia de 1979, acaba por baixa-lo pirata por torrent (como nos bons anos 2005) e sente o peso não apenas do filme em si, mas da expectativa cultural que o envolve como uma mortalha. Quando vi pela primeira vez lá atrás, havia uma pressão por ser comédia de gente inteligente, era o primórdio do sarcasmo, da acidez mas que hoje soam como atuações ingênuas em muitos momentos. Lá naquela época eu ria porque gostava mesmo, acho que na minha mente jovem aquilo era tão anti humor e cáustico (para a época) que soava incrível. Mas agora aqui, no momento presente eu enfrentava uma pressão imensa causada somente por mim mesmo: A pressão para apreciar. E, acima de tudo, a pressão esmagadora para rir. Rir da maneira certa. Aquela risada que é ao mesmo tempo inteligente e visceral, a risada que diz: “Ah, sim, eu captei a referência ao sectarismo da esquerda britânica dos anos 70 E também achei o pênis de um romano com um nome engraçado inerentemente hilário”.

A Vida de Brian, do Monty Python, chega até mim, Millennial de 37 anos não como um filme, mas como um dever de casa. Um artefato cultural cuja fama o precede de tal forma que o ato de assisti-lo pela primeira vez em, digamos, 2025, é menos um ato re-análise e mais um de arqueologia sócio-cultura (que, porra! Só por descambar nisso o filme já se torna entediante, me pergunto quantos filmes de comédia dos quais eu adorava, spoiler: Cara, cadê meu carro; Quem vai ficar com Mary; Superbad; Pineapple Express; Todo Mundo em Pânico, etc, iriam sobreviver ao momento cabeçudo sério, triste e NATURAL, inerente, dos dias de hoje. Enfim, desenterrei com a minha namorada algo que tinha o aspecto de ouro de um tempo passado, mas que, sob a luz fria e implacável de nossas telas de 4K, parece... outra coisa. Um metal diferente, talvez. Latão, possivelmente. Um latão que foi polido com tanto vigor por décadas de aclamação que seu brilho agora parece mais o suor do esforço do que um fulgor genuíno.

E aqui reside, talvez, o núcleo desconfortável da questão, o tipo de verdade que você hesita em admitir em um jantar com pessoas mais velhas e culturalmente mais seguras: na maior parte do tempo, A Vida de Brian não é engraçado. Não de uma forma que produza aquela risada involuntária e ofegante que é a verdadeira marca do grande humor. Em vez disso, ele provoca, na melhor das hipóteses, um aceno de cabeça apreciativo. “Ah, vejo o que eles fizeram ali. Astuto.” E, na pior das hipóteses, e com uma frequência alarmante, provoca um tipo muito específico de desconforto geracional, uma sensação que a linguagem contemporânea, em sua gloriosa falta de sutileza, rotulou de cringe, termos que define muito bem tudo que a inglaterra tentou fazer no humor cinematográfico em 90% do tempo. É um desconforto que se manifesta fisicamente: um leve franzir de sobrancelhas, um encolher de ombros quase imperceptível, o desejo súbito de checar as notificações do celular.

Deixe-me ser brutalmente honestos por um segundo. A piada central do filme, a que lhe dá a espinha dorsal narrativa, é uma premissa de sitcom, não é uma piada ruim. Um caso de identidade trocada. Brian Cohen, um homem perfeitamente comum, nascido na manjedoura ao lado, é confundido com o Messias. É uma ideia brilhante. É o tipo de ideia que, se você a tivesse, correria para anotá-la em um caderno que você nunca mais vai lembrar de re-visitar, mas ao menos garantiu que anotou. O problema não está no conceito. O problema, para o espectador contemporâneo, está na execução incessante, quase frenética, de tudo o que o rodeia. O humor do Python, pelo menos nesta sua encarnação cinematográfica, opera em um volume consistentemente bolorado. É um humor físico, performático. É teatral, cheio de caretas e vozes estridentes. Agora numa distância de quase cinquenta anos, meu comentário talvez fosse um hesitante: “Bem, sim, vocês são inteligentes, eu acho, mas vocês poderiam, por favor, falar um pouco mais baixo?”. Há uma qualidade quase desesperada na forma como muitas piadas são marteladas, como se a mera repetição de um conceito bobo (o nome “Biggus Dickus”, o debate sobre o que os romanos nos deram, a cisão entre a Frente Popular da Judeia e a Frente do Povo Judaico) fosse suficiente para transformá-lo numa masterpiece do humor.

Para uma geração criada com uma dieta de humor que muitas vezes se baseia no subentendido, no dadaismo inconsciente, na ironia em múltiplas camadas e no desconforto social de The Office (americano, porque convenhamos, Office original britânico é PÉSSIMO) ou na desconstrução surreal e melancólica de BoJack Horseman, essa abordagem de força bruta (ou humor late-boomer) parece... estranha. Antiquada. A linguagem mudou. Não a linguagem falada, mas a linguagem semiótica da comédia. O que antes era uma sátira cortante sobre a futilidade do sectarismo de esquerda, hoje parece uma representação tediosamente precisa de um dia médio no Twitter. A paródia foi ultrapassada pela realidade a um ponto em que ela não mais reflete ou exagera o mundo; ela apenas o descreve, mas com sotaques britânicos de homens fazendo voz de mulheres. E o choque do reconhecimento não é mais engraçado; é simplesmente cansativo. E então, é claro, chegamos à questão da Blasfêmia. Com B maiúsculo. A controvérsia original que cimentou o status lendário do filme. Proibido na Noruega, denunciado por grupos religiosos, visto como um ataque corajoso e sem precedentes ao cristianismo organizado. Em 1979, isso era dinamite. Era um ato de transgressão genuína, um soco para cima contra uma instituição monolítica e poderosa. Assistindo hoje, pelos olhos de um ateu que vive em uma sociedade ocidental amplamente secularizada, onde a crítica à religião organizada é um lugar-comum em podcasts, especiais de stand-up e fóruns de internet, o impacto da blasfêmia do filme parece incrivelmente... brando.

O que nos leva, de uma maneira sinuosa e talvez desnecessariamente complicada, à cena que talvez envelheceu da forma mais desconfortável de todas. A cena em que Stan, interpretado por Eric Idle, anuncia seu desejo de ser uma mulher chamada Loretta e de ter o direito de ter bebês. A reação de John Cleese como Reg é de exasperação lógica. “Mas você não pode ter bebês... você não tem um útero!” É apresentada como o auge da sátira à política de identidade levada ao extremo do ilógico.

Essa sensação de descompasso temporal permeia tudo. As piadas visuais, como a perseguição com os alienígenas, parecem inseridas de outro filme, um esboço aleatório que quebra o que quer que seja o ritmo diegético que a narrativa estava tentando construir. A própria estética, com sua paleta de cores marrom e bege da Judéia filmada na Tunísia, embora autêntica, contribui para uma sensação de distância, de secura. É um filme que você admira mais do que gosta, afinal, naqueles anos os atores atuavam, corriam, se mexiam, os cenários eram reais, habia cenografia detalhada, muita mão de obra, força de trabalho em prol de uma obra, tudo isso parece agora quase como um museu do cinema (imagino como seria assistir um Ben-Hur da época). O clímax, a famosa cena da crucificação com a canção “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life”, é talvez o momento em que o filme chega mais perto de alcançar a transcendência que lhe é atribuída. É uma justaposição brilhante de horror e alegria, um hino ao estoicismo diante do aniquilamento. Blá blá blá, mas ao mesmo tempo talvez minha hanedonia e sono de fim de filme tirou qualquer encanto sincero, parece que sempre escorregavam antes de alcançar o climax das piadas.

Enfim, a experiência de assistir A Vida de Brian foi como visitar uma casa de infância que foi vendida para novos donos. A estrutura ainda está lá. Você reconhece a arquitetura. Você pode ver onde as coisas costumavam ficar. Mas os móveis são todos diferentes, há um cheiro estranho no ar e você se sente um intruso. O filme se tornou um monumento a um tipo específico de humor — um humor de colarinho branco, educado em Cambridge, que se deleitava em sua própria inteligência e usava o absurdo como uma arma contra o establishment. Os Pythons eram, de fato, Boomers muito à frente de seu tempo. Tão à frente, talvez, que eles chegaram a um futuro que nós agora habitamos, mas não previram que, quando chegássemos, já teríamos ouvido todas as suas piadas antes, contadas de formas diferentes, em contextos diferentes, por pessoas que viram o que eles fizeram e construíram em cima disso, ou simplesmente viram a realidade se tornar mais estranha do que qualquer paródia que eles pudessem conceber. Não há alegria em declarar um clássico como datado. Parece um sacrilégio, uma falha do próprio espectador. “Talvez o problema seja eu”, cheguei a pensar. “Talvez eu não esteja mais inteligente o suficiente. Talvez eu tenha sido irremediavelmente corrompido pela internet.” E talvez haja um pouco de verdade nisso. Mas talvez a verdade maior seja que a comédia, mais do que qualquer outra forma de arte, é perecível e envelhece como leite. Ela depende de um contrato tácito com seu público, um conjunto compartilhado de normas, ansiedades e alvos. Quando esse contrato expira, o que resta não é mais uma piada viva, mas o fantasma de uma. E A Vida de Brian, com todo o seu brilhantismo inegável e sua importância histórica, parece agora assombrado por esses fantasmas. Rimos, quando rimos, não do filme em si, mas do eco de uma risada de quase meio século atrás, uma risada que podemos reconhecer, admirar, mas que, para nossa frustração e talvez um pouco de tristeza, simplesmente não conseguimos mais sentir como nossa. No final das contas foi bom ver pra saber que não é bom como um dia já foi.

Nota: 3/10

Obrigado pela leitura!

Thomas Blum

Obrigado por promover a comunidade Hive-BR em suas postagens.

Vamos seguir fortalecendo a Hive

Eis aqui um clássico que eu nunca me dei ao trabalho de assistir por completo (na época, pela péssima qualidade da mídia mesmo... então eu acabei assistindo apenas 1/3 do filme e não tive mais paciência), mas eu tive a impressão de que o roteiro envelheceu "mal" considerando o que a sociedade moderna entende por "engraçado".

Pois é meu caro! E olha, eu não sou um "militante" chato com essas coisas culturais e sociais, eu considero que tenho um humor bem afiado (talvez exigente, sim), não é só por causa do mal envelhecimento de certas piadas não, apesar que isso contou pontos, por que é como confrontar um fantasma de si, mas por que simplesmente as piadas são fracas e ingênuas mesmo, muito esforço pra pouca graça. Tem sim bons momentos, e quem sabe revendo os outros filmes eu ia achar que são melhores, mas esse daí infelizmente me decepcionou nessa revisita.

Sending you some Ecency curation votes!

Thank Youuu!

a good sense of humor is very good attribute to have

Only a Three out of ten? Yikes! I am indeed of a different generation.

Heheh. I understand you completely. I don't know how old you are, but I'm 37 and I have serious problems with the humor of generation Z (imagine Alpha), I'm a self-confessed millennial and I experienced the rise of the chaotic and almost dadaist humor of the internet. I saw all the Python movies even before the internet was ubiquitous in people's lives and at the time the grade I would have given would probably have been an 8/10...

The question is, have I lost my sense of humor or have they become naive and unfunny? I'd say it's both. And look, I swear I'm not a "super progressive" who tries to problematize cultures and say that X or Y thing is in bad taste, I rarely do that, but there are things that simply age badly, unfortunately.

We're the same age! (Almost!)

I loved the chaotic humor of the early Internet. I still do. That old Internet doesn't really live on anymore. All those flash animations, all those early artefacts that were burnt from cd to cd and circulated among friends.

I too saw those Python films early. I think I didn't understand them at first, the animated interludes, the language and the way it was used.

It wasn't until a few years on that I could really sit back and laugh at the films and the Pythonesque comedy.

It may have something to do with culture, too - I'm Australian, and our humor is very dead pan, dark, and direct. The British humor is often more slapstick, boring, and quite ... unsophisticated?

While I loved The Life of Brian and think it is definitely a lot better than 3/10 I would say that Monty Python as a whole is kind of over-revered as a comedy troope. I was once very excited to get my hands an the "complete Monty Pyton" DVD set to borrow from a friend only to discover that much like Key and Peele or SNL, or really any comedy variety something or other, most of what they did wasn't funny at all. Sure, there are some standout things that the "best of" would probably do a good job of making us believe that everything they did was just the funniest thing ever, but that simply isn't the case when it was made, and it certainly isn't now.

I think a lot of people that claim they LOVE Monty Python say so in order to be different: A vast majority of what they made is mid at best.

Exactly! I think that back when it was still "hot", it wasn't really funny anymore, at least not at the level of expectation that was created. And I don't say that without knowledge, I've seen a good part of the TV series box set, I've seen all the movies, I "liked" it, but it all seems very weak and boring nowadays. Maybe my rating was too low, but I think it was more due to the disappointment of this update...

Congratulations @thomashnblum! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain And have been rewarded with New badge(s)

Your next target is to reach 26000 upvotes.

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOP